05 January 2015

Simulating a financial exchange in Scala

There are two hard things in computer science: cache invalidation, naming things, and off-by-one errors – [Phil Karlton] (http://martinfowler.com/bliki/TwoHardThings.html)

Picking the right project to learn a new language can be a frustrating experience. “Hello world” is an old tradition but to really get a feel for a new language, a project has to be large enough to touch various language structures, but small enough to be written in a few days. My first project in Scala implements a core part of a financial exchange called an order book.

Financial markets and automated trading have been in the news lately. Discussions involving the industry often show a lack of understanding of the mechanics of markets. I will use this post to describe the basics of how a central component of financial markets, the financial exchange, works.

I will attempt to describe the basic set of rules used to match orders. I will also show the mechanics of how and why the price of an instrument might change second to second. Most of these concepts will also be implemented in Scala.

Programmers familiar with the trading industry should keep in mind that I have only implemented the bare minimum to learn Scala, this is obviously no where near production level code. There are certain missing pieces I will specifically mention. However, if I have made a mistake in some concept, please send me a note.

What are financial exchanges?

Stock exchanges, or more generally financial exchanges, are market places where buyers and seller exchange goods. Think of a farmers’ market: you go there to buy fresh produce, you can also set up a table there to sell your own veggies. If you are a seller, you may put up a sign listing the price of your lettuce. However, as the day goes on, you may adjust your price according to how many customers are coming to your table or how other sellers and pricing their produce. If you are a buyer, your desire to buy and your purchase price may also change as you see what is being offered and how other buyers are behaving.

Let’s strain this analogy between farmers’ market and a stock market a bit. Assume that all produce is exactly the same. All the lettuce is identical and all apple stalls provide exactly the same customer service. If price was the only differentiating factor, the most convenient thing for a buyer would be a single number: the lowest price. Sellers will also want to find the customer willing to pay the highest price, and not much more.

Think of a stock exchange similarly. A large number of buyers and sellers gather to buy or sell AAPL, GOOG, MSFT, IBM or any other stock. Instead of hundreds of buyers and sellers, what if there were tens of thousands? Given that one share of AAPL common stock is the same as any other, what would you do, as the stock market organizer, to facilitate the greatest number of transactions (meaning as many buyers are able to buy and as many sellers are able to sell as possible)?

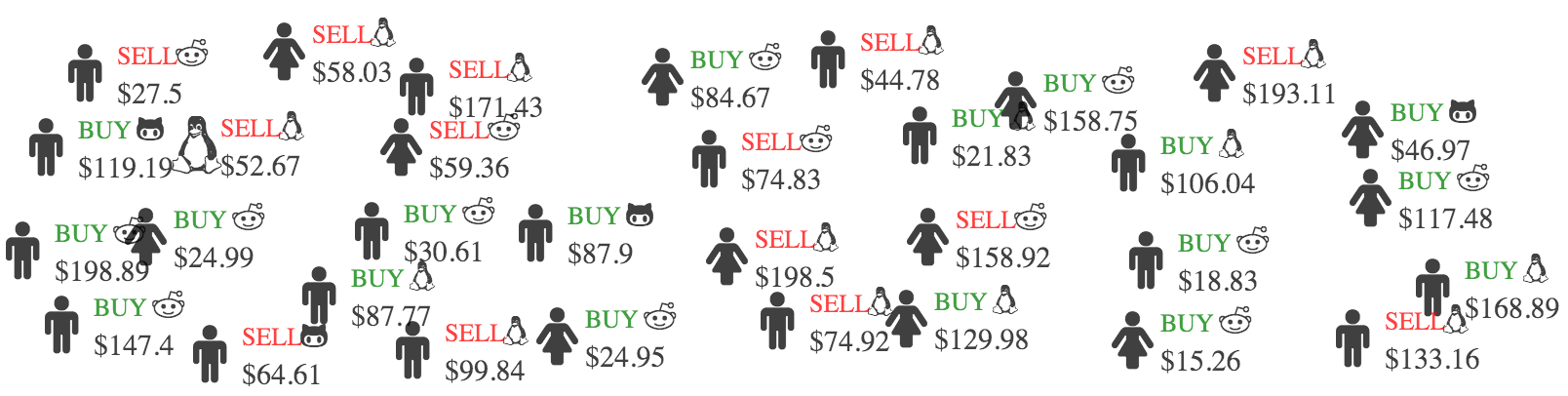

Market where nothing is organized, all stocks are trading together

First, let’s move each stock to its own area. MSFT buyers and sellers in room 1A, IBM buyers and sellers in room 3C, etc. This makes it much simpler to compare prices.

Only Reddit “stock” being traded here

Next, let’s create two lines, one of buyers and one of sellers. Have them stand in order of the price at which they are willing to do the transaction. Buyers stand in ascending order (the higher the price you are willing to pay, closer you are to the head of the line). Sellers stand in descending order (the lower the price at which you are willing to sell, closer you are to the head). People are welcome to get ahead or move behind by changing their price.

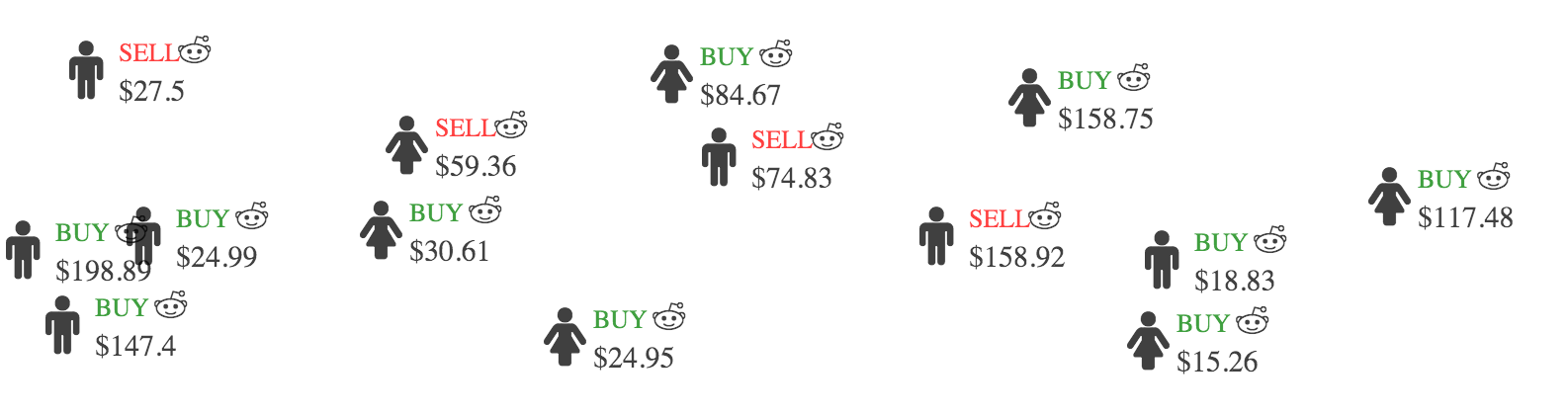

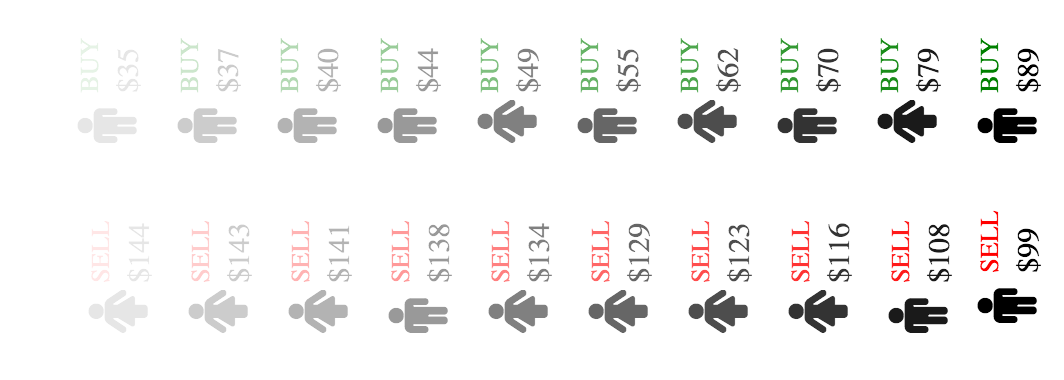

Buyers and sellers in the own lines, standing in order of price

Notice that buyers stand in line in a way that prices increase closer to the head of the line. Sellers, however, stand in opposite order. Their prices decrease closer to the head of the line. The two, in a manner of speaking, meet in the middle. The bids (prices buyers are willing to pay) are always less than the offers (prices at which sellers are willing to sell). This is the natural consequence of what markets are. If a bid was equal to or higher than an offer, the buyer and the seller would immediately do the transaction and disappear from the picture. Let’s visualize the crowd along a single line of increasing prices, from left to right.

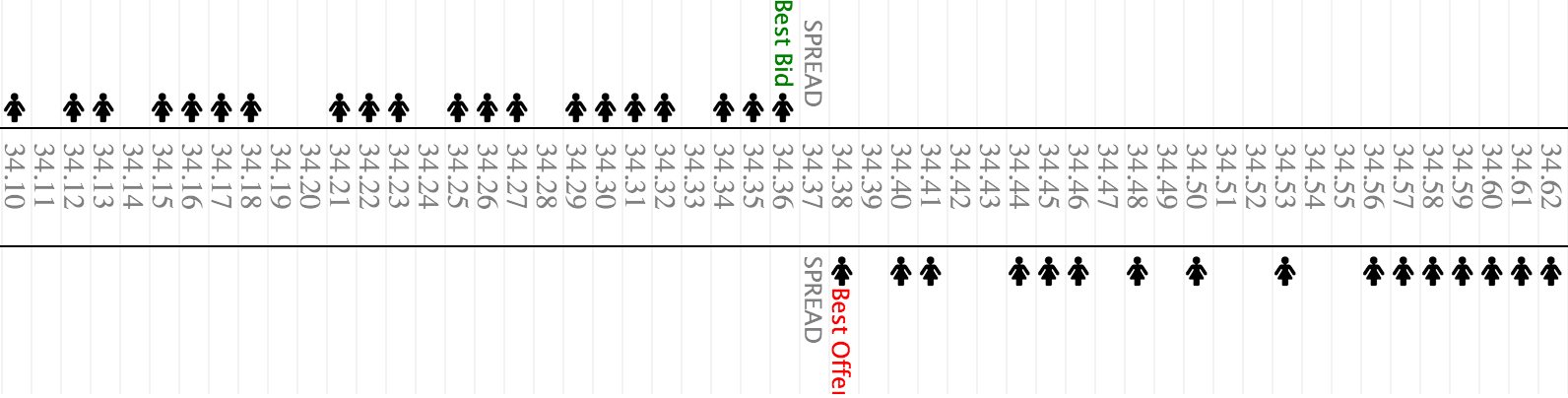

Single line with prices, more naturally shows how buyers and sellers line up

Market mechanics

Let’s step through how an order is matched.

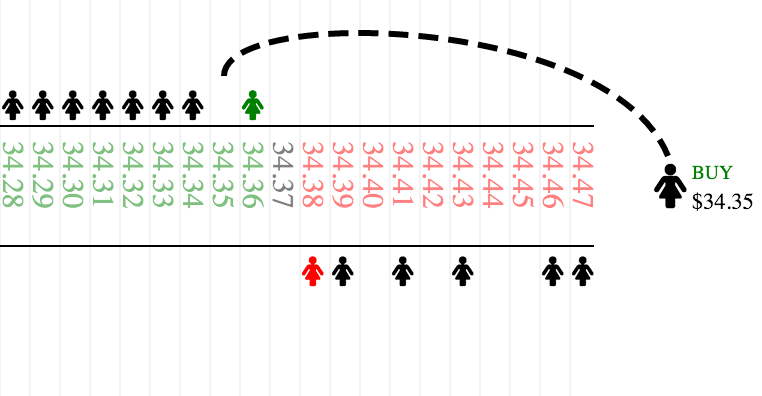

Buyer’s order isn’t matched so she takes her place in line

If a new buyer comes into the market and wants to buy a stock for $34.35, but the lowest price at which it is being offered is $34.38, there is no match and the buyer gets in line among the buyers.

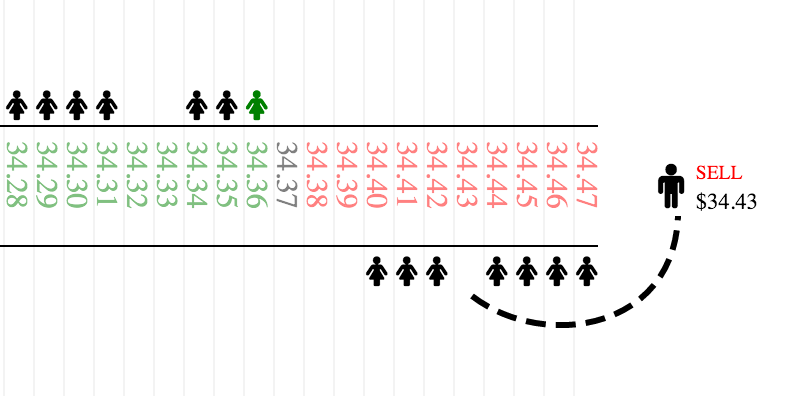

Seller’s order isn’t matched, so she takes her place in line

Similarly, if a new seller wants to sell their stock at no less than $34.43, but there are no buyers at that price, the seller gets in line.

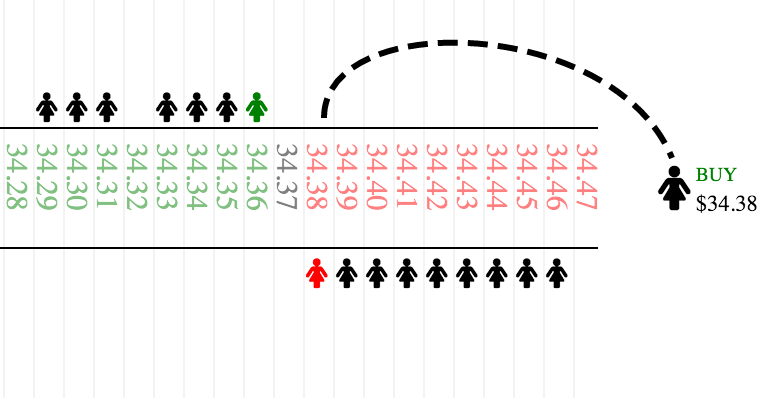

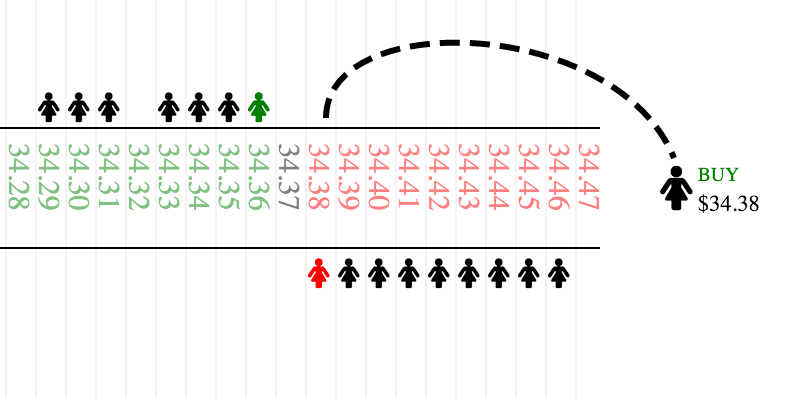

Buyer is willing to pay what a seller is charging, matched!

If a buyer is willing to pay $34.38 and there is a seller at that price, a match is found and the trade occurs.

That’s the basic idea. Details are a bit more complicated. If a buyer was looking to buy a 1,000 shares, but the seller only had 100 to sell, the buyer would just go down the line of buyers, buying up all the shares he needed. If the buyer wanted to pay no more than $540 but the seller wanted at least $560, the two would just stand there, looking at each other until someone else decided to change their location in the line. This post will keep things simple.

Why do prices change?

Let’s step back a bit. Why was the seller willing to sell at $34.43/share? How did she arrive at the price? How did the buyer arrive at his price? Why are there other people in the line buying and selling at different price? In other words, why would someone choose to not be at the head of the line?

Of course, we can’t read the minds of our hypothetical buyers and sellers, but let’s make some common sense guesses. The most obvious reason for someone to decide on a price is simply because others are also doing transactions at that price. As I type this, MSFT is at $47.88 and AAPL is at $113.99. I have no idea why, but if I expect the next version of Windows to bring unprecedented profits to Microsoft, I’ll invest in their stock at the current price and hope to profit.

Another person could have done a great deal more analysis, looked over AAPL books and decided that it is worth 700 billion dollars as a company. Since there are around 5.8 billion shares of AAPL in the market, the stock price should be around $120 (company value / outstanding shares). Since AAPL is actually trading at $113.99, if I am certain of my analysis, I’ll load up on AAPL and be willing to pay any price, up to, say, $118.

Someone who bought XYZ when it ws three dollars cheaper is now ready to sell at the current price, they want to take their profit and buy a TV. Someone else is fed-up with the ethics of company ABC and wants to dump their shares of it as a matter of principal. Yet another person just inherited some money and buys a mutual fund, which, in turn, invests that money in a diversified portfolio.

The investors mentioned so far were basing their decisions to buy or sell on the company itself. There is another group of traders who couldn’t care less about the company behind the acronym. Imagine you are back at the stock exchange where different rooms are setup to trade different stocks. All day prices rise and fall by a penny or two because someone’s grandma left them some money or someone else friend told them about horrible business practices at whatever company. Every once in a while, you hear a commotion near some room. Initially, there are slightly more people in the room than usual, then the price starts moving in some direction, more people rush in to see what’s going on. As the price trend continues, the bystanders decide to bet in the direction of the market. They don’t know why the price is moving, but, to them, it looks like they will be able to eek out a profit before the trend is finished. As those people enter the market, the price trend becomes even stronger, attracting an even greater number of participants. Most of these people don’t care about the underlying value of the company, they are simply speculating on the price.

We can see how the madness (or rational decision making?) leads to short term trends, but what might be the starting point of this panic or euphoria? I have no idea, but some common sense reasons might be the following: sudden need for cash may result in rapid selling of a portfolio, which results in price of a stock changing, even when the company behind the stock has done nothing new. If a large number of foreigners hold some stock, fluctuation in currency prices can cause holders of a stock to flee (or rush in).

We have seen investors and speculators. There is yet another group which focuses not on a particular price, but relationships among prices. For example, Toyota is not only traded in Japan. If the price of Toyota is $128 in New York, but $130 in Tokyo, what is the natural thing to do? Buy it in NYC and sell it in Tokyo! When prices come back in line, unwind your position. Notice that by taking advantage of such arbitrage, you have not only made money for yourself, this act of buying and selling actually helped bring the two prices closer together. Let’s look at the actual mechanics of it next.

How do prices change?

Buyer is willing to pay what a seller is charging, matched!

Take another look at the diagram which shows a pair of traders getting a match. A new buyer enters the market and is matched against a seller who was offering their stock at $34.38. What happens after the match is done? If there was no one else offering their stock at $34.38, the best offer would move up a penny to $34.39.

In this scenario, a single buyer, could have been you, managed to change the price of a stock. There was no central authority managing the price. There is no explicit, centralized, mechanism to keep prices at a certain level. The price of a stock moved because the person offering the stock at $34.38 was bought out by some anonymous buyer.

This post hasn’t discussed the role of order sizes. I have made a simplifying assumption that every one is interested in buying or selling the same quantity. However, what if the person buying stock wanted more than what was being offered by the top seller? What if the buyer was willing to pay a few pennies more? The matching algorithm would simply go down the list of sellers and buy as much stock as required by the buyer (up to the buyer’s price limit).

This action of ‘sweeping the book’ has the consequence of rapidly changing the price. Rather than stock jumping around by a penny, a large order, or a large number of traders on either side of the market can ‘move’ the market in the opposite direction. A large buyer will raise the price of a stock and a large seller will reduce the price.

This leads to a whole industry of algorithms designed to reduce such market impact. An interesting topic, but out of scope here.

How to implement an order book?

Let’s, finally, take a look at some code.

Common events

An order book expects to receive three kinds of requests: a request to submit a new order, a request to cancel a previously entered order and a request to amend an existing order.

abstract class OrderBookRequest

case class NewOrder(timestamp: Long, tradeID: String, symbol: String, qty: Long, isBuy: Boolean, price: Option[Double]) extends OrderBookRequest

case class Cancel(timestamp: Long, order: NewOrder) extends OrderBookRequest

case class Amend(timestamp: Long, order:NewOrder, newPrice:Option[Double], newQty:Option[Long]) extends OrderBookRequest

The order book responds with an acknowledgement of a new order, notification that it was filled (partially or completely), rejected or canceled.

abstract class OrderBookResponse

case class Filled(timestamp: Long, price: Double, qty: Long, order: Array[NewOrder]) extends OrderBookResponse

case class Acknowledged(timestamp: Long, request: OrderBookRequest) extends OrderBookResponse

case class Rejected(timestamp: Long, error: String, request: OrderBookRequest) extends OrderBookResponse

case class Canceled(timestamp: Long, reason: String, order: NewOrder) extends OrderBookResponse

An order book also needs to notify when an execution occurs or when the best bid or offer changes. In the code below, BBOChange refers to “best bid or offer change.”

abstract class MarketDataEvent

case class LastSalePrice(timestamp: Long, symbol: String, price: Double, qty: Long, volume: Long) extends MarketDataEvent

case class BBOChange(timestamp: Long, symbol: String, bidPrice:Option[Double], bidQty:Option[Long], offerPrice:Option[Double], offerQty:Option[Long]) extends MarketDataEvent

Order Book … book keeping

The OrderBook class, itself, contains two priority queues, one for bids and one for offers. Naturally, the queues are ordered according to price. The class defines its own ‘Order’ object. While the requests sent by clients are never modified, the Order object is private to the Order Book class and can be modified.

This class also contains basic infrastructure for keeping track of subscribers to various event types. See note near end regarding Akka, a concurrency library which, among other things, manages subscriptions.

class OrderBook(symbol: String) {

case class Order(timestamp: Long, tradeID: String, symbol: String, var qty: Long, isBuy: Boolean, var price: Option[Double], newOrderEvent:NewOrder)

val bidOrdering = Ordering.by { order: Order => (order.timestamp, order.price.get)}

val offerOrdering = bidOrdering.reverse

//Needed for java.util.PriorityQueue

val bidComparator = new Comparator[Order]{

def compare(o1:Order, o2:Order):Int = bidOrdering.compare(o1,o2)

}

val offerComparator = new Comparator[Order]{

def compare(o1:Order, o2:Order):Int = offerOrdering.compare(o1,o2)

}

//val bidsQ = new mutable.PriorityQueue[NewOrder]()(bidOrdering)

//val offersQ = new mutable.PriorityQueue[NewOrder]()(offerOrdering)

//scala PQ doesn't let me remove items, so must revert to Java's PQ

val bidsQ = new PriorityQueue[Order](5,bidComparator)

val offersQ = new PriorityQueue[Order](5,offerComparator)

var bestBid: Option[Order] = None

var bestOffer: Option[Order] = None

var volume: Long = 0

var transactionObserver: (OrderBookResponse) => Unit = (OrderBookEvent => ())

var marketdataObserver: (MarketDataEvent) => Unit = (MarketDataEvent => ())

Process incoming requests

Method ‘processOrderBookRequest’ is the main method which receives requests sent to this object. In an actor system, this would be the ‘receive’ method. This method generally delegates all complex logic to other methods in the class.

def processOrderBookRequest(request: OrderBookRequest): Unit = request match {

case order: NewOrder => {

val currentTime = System.currentTimeMillis

val (isOK, message) = validateOrder(order)

if (!isOK) this.transactionObserver(Rejected(currentTime, message.getOrElse("N/A"), order))

else {

this.transactionObserver(Acknowledged(currentTime, order))

val orderBookOrder = Order(order.timestamp,order.tradeID,order.symbol,order.qty,order.isBuy,order.price,order)

processNewOrder(orderBookOrder)

}

}

case cancel:Cancel => {

val order = cancel.order

val orderQ = if (order.isBuy) bidsQ else offersQ

val isRemoved = orderQ.remove(order)

if(isRemoved){

this.transactionObserver(Acknowledged(System.currentTimeMillis(),cancel))

updateBBO()

}

else this.transactionObserver(Rejected(System.currentTimeMillis(),"Order not found",cancel))

}

case amend:Amend => {

val order = amend.order

val orderBookOrder = Order(order.timestamp,order.tradeID,order.symbol,order.qty,order.isBuy,order.price,order)

val orderQ = if (order.isBuy) bidsQ else offersQ

val oppositeQ = if (order.isBuy) offersQ else bidsQ

if(!orderQ.remove(orderBookOrder)){

this.transactionObserver(Rejected(System.currentTimeMillis(),"Order not found",amend))

}

else{

if(amend.newQty.isDefined) orderBookOrder.qty = amend.newQty.get

if(amend.newPrice.isDefined) orderBookOrder.price = amend.newPrice

orderQ.add(orderBookOrder)

this.transactionObserver(Acknowledged(System.currentTimeMillis(),amend))

updateBBO()

}

}

}

Process new orders, the most important kind of orders

‘processNewOrder,’ as the name implies takes on the task of processing requests to enter new order into the order book. It does some basic book keeping, such as setting up the order queue, queue of the opposite side, etc. Unless the order needs to be rejected, ‘matchOrder’ is called to actually carry out the logic of matching orders.

def processNewOrder(orderBookOrder: Order) {

val currentTime = System.currentTimeMillis

val orderQ = if (orderBookOrder.isBuy) bidsQ else offersQ

val oppositeQ = if (orderBookOrder.isBuy) offersQ else bidsQ

if (orderBookOrder.price.isDefined) {

//=====LIMIT ORDER=====

if (oppositeQ.isEmpty || !isLimitOrderExecutable(orderBookOrder, oppositeQ.peek)) {

orderQ.add(orderBookOrder)

updateBBO()

}

else {

matchOrder(orderBookOrder, oppositeQ)

}

}

else {

//=====Market order=====

//TODO: what if order was already partially executed, replace reject with partial cancel?

if (oppositeQ.isEmpty) this.transactionObserver(Rejected(currentTime, "No opposing orders in queue", orderBookOrder.newOrderEvent))

else matchOrder(orderBookOrder, oppositeQ)

}

}

private def validateOrder(order: NewOrder): (Boolean, Option[String]) = (true, None)

Order matching logic

Method ‘matchOrder’ carries out the logic (partially) diagrammed above. Unlike the diagram, it does order size management. For example, if the order size is larger than what is made available by the top buyer or seller, the match needs to occur for the number of shares available and the matching algorithm needs to be called recursively for the remaining shares.

private def matchOrder(order: Order, oppositeQ: PriorityQueue[Order]): Unit = {

val oppositeOrder = oppositeQ.peek

val currentTime = System.currentTimeMillis()

if (order.qty < oppositeOrder.qty) {

oppositeOrder.qty = oppositeOrder.qty - order.qty

this.volume += order.qty

this.transactionObserver(Filled(currentTime, order.price.get, order.qty, Array(order.newOrderEvent, oppositeOrder.newOrderEvent)))

this.marketdataObserver(LastSalePrice(currentTime, order.symbol, order.price.get, order.qty, volume))

updateBBO()

}

else if (order.qty > oppositeOrder.qty) {

oppositeQ.poll

val reducedQty = order.qty - oppositeOrder.qty

order.qty = reducedQty

this.volume += order.qty

this.transactionObserver(Filled(currentTime, order.price.get, order.qty, Array(order.newOrderEvent, oppositeOrder.newOrderEvent)))

this.marketdataObserver(LastSalePrice(currentTime, order.symbol, order.price.get, order.qty, volume))

updateBBO()

processNewOrder(order)

}

else {

//TODO: doing an '==' on doubles is a BAD idea!

oppositeQ.poll

this.volume += order.qty

this.transactionObserver(Filled(currentTime, order.price.get, order.qty, Array(order.newOrderEvent, oppositeOrder.newOrderEvent)))

this.marketdataObserver(LastSalePrice(currentTime, order.symbol, order.price.get, order.qty, volume))

updateBBO()

}

}

Notify the world

Method ‘updateBBO’ exists to abstract out logic which is repeatedly called all over the code. Whenever the price (or size) of the top seller or buyer changes, OrderBook needs to inform its clients.

private def updateBBO() = {

val bidHead = Option(bidsQ.peek)

val offerHead = Option(offersQ.peek)

if(bidHead != bestBid || offerHead != bestOffer){

bestBid = bidHead

bestOffer = offerHead

var bidPrice:Option[Double]=None

var bidQty:Option[Long]=None

var offerPrice:Option[Double]=None

var offerQty:Option[Long] = None

//TODO: Does scala have some sort of monad magic to get rid of these, essentially, nested null checks?

if(bestBid.isDefined){

bidPrice = bestBid.get.price

bidQty = Some(bestBid.get.qty)

}

if(bestOffer.isDefined){

offerPrice = bestOffer.get.price

offerQty = Some(bestOffer.get.qty)

}

this.marketdataObserver(BBOChange(System.currentTimeMillis, this.symbol, bidPrice, bidQty, offerPrice, offerQty))

}

}

private def isLimitOrderExecutable(order: Order, oppositeOrder: Order): Boolean = {

if (order.isBuy) order.price.get >= oppositeOrder.price.get

else order.price.get <= oppositeOrder.price.get

}

The main thing…

The following listing is the ‘public void main’ method of Scala and actually executes a few scenarios.

object Main extends App {

val random = new scala.util.Random

val msftBook = new OrderBook("MSFT")

msftBook.listenForEvents((response) => {

response match {

case resp => println(resp)

}

})

msftBook.listenForMarketData((response) => {

response match {

case resp => println(resp)

}

})

//one bid, only bidQ should be populated

val order1 = NewOrder(1, "1", "MSFT", 100, true, Some(50))

msftBook.processOrderBookRequest(order1)

assert(!msftBook.bidsQ.isEmpty)

assert(msftBook.offersQ.isEmpty)

//execute 50 shares of the order in bidsQ

val order2 = NewOrder(1, "2", "MSFT", 50, false, Some(50))

msftBook.processOrderBookRequest(order2)

assert(msftBook.bidsQ.peek.qty == 50)

assert(msftBook.offersQ.isEmpty)

//offer shares at a price where both bid and offer queues are populated with 50 shares

val order3 = NewOrder(1, "3", "MSFT", 50, false, Some(51))

msftBook.processOrderBookRequest(order3)

assert(msftBook.bidsQ.peek.qty == 50)

assert(msftBook.offersQ.peek.qty == 50)

}

Full code available on [github] (https://github.com/falconair/SimpleFinancialExchange)

CTRL+F and no mention of concurrency

A developer who wants to join the modern trading industry must learn about performance and concurrency. While Silicon Valley measures performance interms of scalability or throughput, Wall Street measures it in terms of latency and consistency.

Unlike a social network, there usually aren’t millions of clients being served by a service provider. While exchanges broadcast and trading firms may ingest millions of messages per second, the most important metric is the time it takes for a message to leave an exchange until someone reads it, makes a decision on it, and sends a request back to the exchange. Secondly, this latency must be fairly consistent. If 70% of the decisions are taken in under a milli-second, but the remaining 30% takes hundreds of milliseconds (garbage collection, I’m looking at you), firms can (and do) lose money.

One of the reasons I took up this project was to build a foundation in Scala to pick up the actor model (eralier attempts at Erlang failed). The Akka library has a great deal of buzz. Being a fairly high level library, I suspect that it won’t perform as well in low latency scenarios as it might in high throughput and high scalability settings. Nevertheless, high productivity and the ability quickly write proof-of-concept code is immensely beneficial on its own.

I’ll leave experiments with Akka to another time, perhaps after a couple more projects with serial code. Learning the syntax, new programming paradigms, new libraries, etc. is quite enough for a first project.

So, is Scala good?

I first looked at Scala years ago, probably around the time it was first released. I had discovered functional programming and programming language theory at [Lambda The Ultimate] (http://lambda-the-ultimate.org) and was trying to make sense of Haskell, O’Caml, Oz, Scheme/Lisp, Erlang, etc. Back then I did’t much like the syntax of the language and moved on. In the intervening years Scala has started to pop up every where, including the trading industry (in non-performance critical systems, in my experience).

While poking around Scala, I gained a great deal of respect for the experts working on the language. They were combining ideas from the very academic side of computer science to the very practical side of industry (the jvm!). Years ago I read a tutorial called “Scala By Example,” by the author of the language, Martin Odersky. One of the chapters of the 100 or so page booklet was on concurrency. He started with the most basic locks and built layer upon layer, until he presented an implementation of the Actor library. Other chapters included an implementation of the Hindley/Milner type inference system and a chapter on parser combinators (although this chapter is no longer in the latest versions). This was one of the best programming language books I had read, certainly better than most other giant texts introducing languages.

My first impression, after actually writing a few hundred lines of code (this project and the next) is that syntax is ok once one has written a few lines. I would have preferred Haskell or F# style syntax, but I adapted to Scala’s style fairly quickly.

Scala is quite a complex language. This is one of those language where learning to use it correctly requires reading a book or two. I’m still not quite sure how implicits work, how type safe the Akka library is and how to correctly constrain type parameters. However, I’m not sure if the complexity comes from the language or if I’m mis-calculating my position on the learning curve.

I was a bit disappointed in the IDE support for Scala. I wrote code in the Intellij plugin for Scala as well as Eclipse. The Intellij plugin kept showing errors which didn’t show up when I manually compiled the code. Eclipse was much better at showing the correct errors, but not very user friendly with the inferred types it showed on mouse hover. Scala’s dark theme looks beautiful while Eclipse looks like eclipse.

While writing this code around Christmas, I found people on the #scala irc channel were extremely helpful and friendly. Even during the holiday season, there were always people there to help debug code.

I certainly wouldn’t recommend Scala for those who are new to programming. Experienced programmers, who have absolutely no experience with functional programming should find that Scala is a great way to start. Unlike Haskell’s laziness and purity or lisp’s syntax, Scala’s ‘obscure’ features such as algebraic data types, implicits and higher order function heavy libraries can be introduced more gradually.

I’m not sure if Scala will ever be among my favorite languages, but I am certainly looking forward to doing a few more projects in the language. I’m glad to see there are commercial companies forming around the language and that it is gaining more acceptance in industry than Haskell was ever able to.

Updated Jan 28, 2015: Added headings to section which describes code.

Let me know!

Checkout http://forum.targetcompid.com. A community site by and for trading technologists.